Key Findings From The 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index

Transparency International has released its 29th annual Corruption Perceptions Index, revealing that corruption levels are thriving across the world.

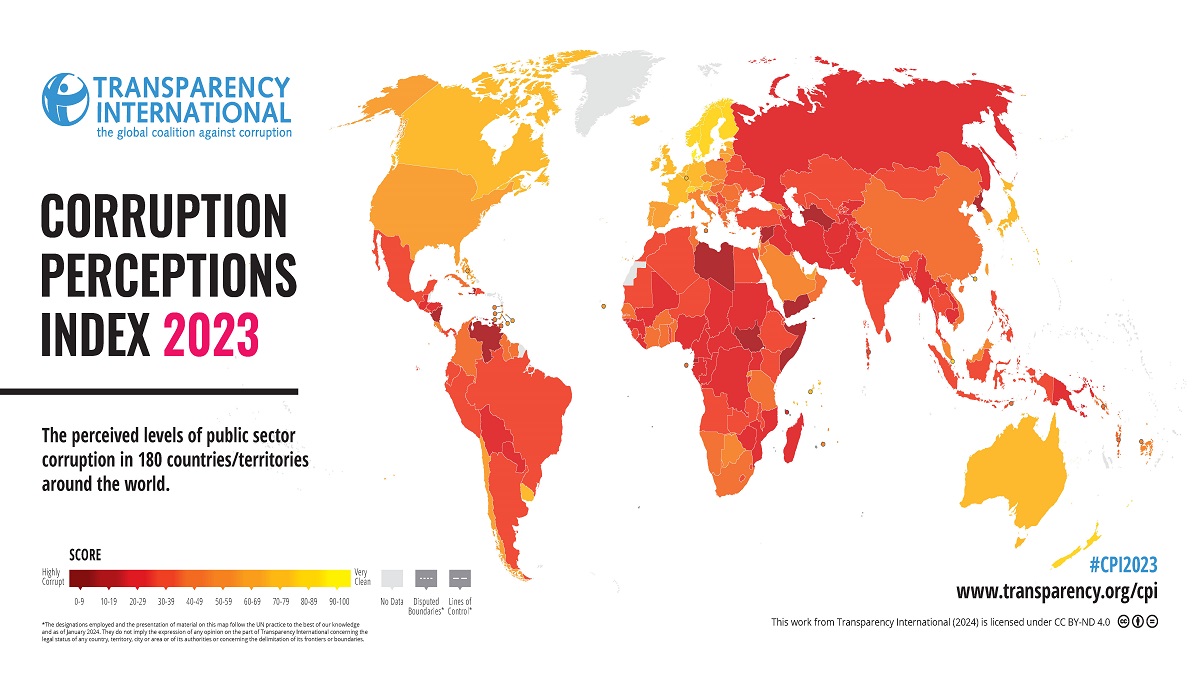

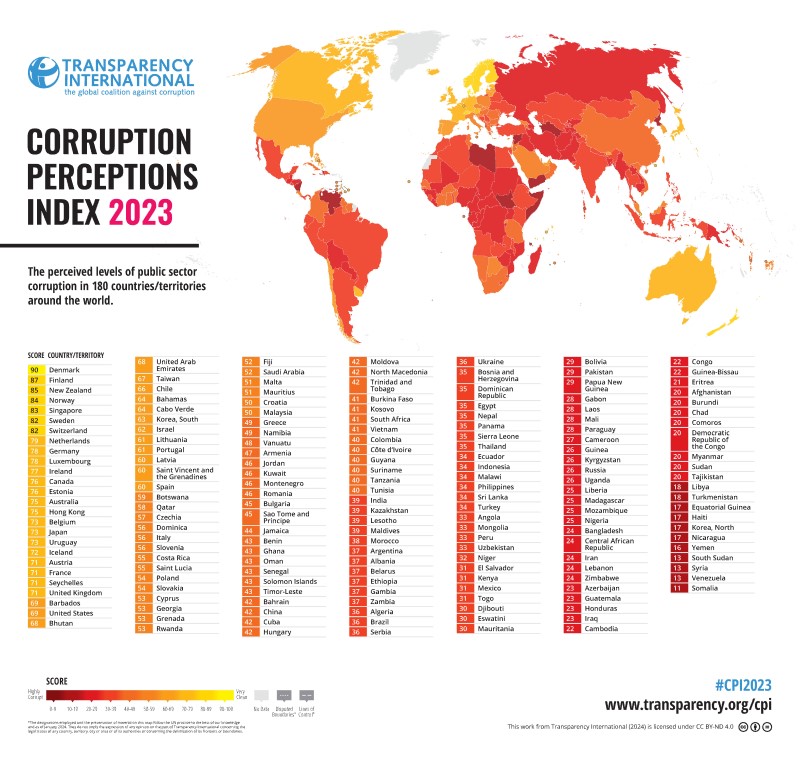

Berlin-based NGO Transparency International has released its 29th annual Corruption Perceptions Index which ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption on a scale of zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The research found that most countries have made little to no progress tackling public sector corruption with the average global CPI score remaining unchanged for the twelfth year in a row.

Global developments in a nutshell

Rising authoritarianism in some countries and a decline in the functionality of justice systems reduced accountability for public officials and allowed corruption to thrive across the world last year, according to the 2023 CPI. Both authoritarian and democratic leaders have undermined justice, encouraging corruption and eliminating consequences for criminals.

The research found that every global region is stagnant in its anti-corruption efforts or showing signs of decline. Only 28 of the 180 countries measured by the index managed to improve their corruption levels over the past 12 years with a further 34 experiencing a significant deterioration in their scores.

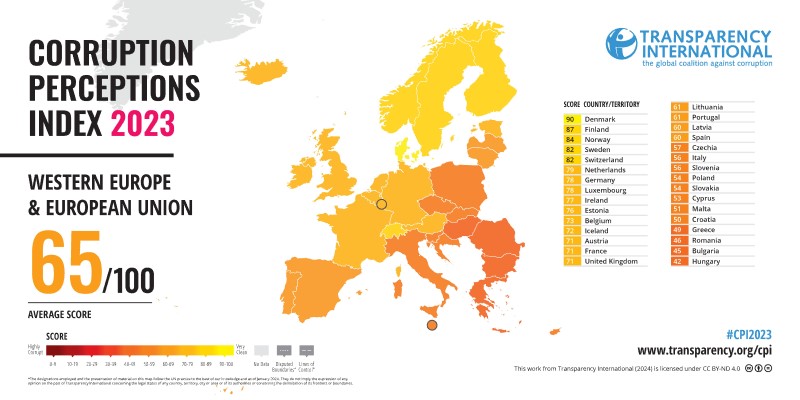

In Western Europe, traditionally the CPI’s best performing region, the score fell for the first time in almost a decade. This is primarily due to a weakening of checks and balances that have undermined robust anti-corruption measures. Weak rule of law and a lack of judicial independence have contributed to widespread impunity in the Americas while historically high-scoring countries in the Asia Pacific region are backsliding.

The Eastern Europe and Central Asia region is struggling with systemic corruption, the dysfunctional rule of law and rising authoritarianism while the Middle East and North Africa has shown little improvement amid conflict and political corruption. Despite some governments experiencing improvement, Sub-Saharan Africa remains the lowest scoring region in the index. Countries with low scores towards the bottom of the ranking mostly tend to experience conflict, have weak institutions and endure highly restricted freedoms.

A closer look at the country scores

The scale of corruption is enormous, and the global average has now remained unchanged for the twelfth year running. Two thirds of countries scored 50 out of 100 or below while the global average was just 43 out of 100. Once again, 2023 saw Denmark, Finland and New Zealand named as the cleanest countries in the ranking, scoring between 85 and 90. With a score of just 11, Somalia was rock bottom of the 2023 CPI.

Top scoring countries

- Denmark

- Finland

- New Zealand

- Norway

- Singapore

Bottom scoring countries

- Somalia

- Venezuela

- Syria

- South Sudan

- Yemen

Anti-corruption efforts undermined in Western Europe

As has been the case historically, Western Europe and the European Union once again topped the 2023 CPI with an average score of 65 out of 100. Despite being the cleanest global region and the introduction of measures such as the EU Whistleblowing Directive, the average score has declined for the first time in almost a decade, albeit by a single point. Along with the weakening of checks and balances that have undermined robust anti-corruption measures, public trust has been dented by weak accountability and political corruption. This has also allowed narrow interest groups to exert excessive control over political decision-making.

Several traditionally high-ranking democracies have seen their corruption scores slide and Sweden (82), the Netherlands (79), Iceland (72) and the United Kingdom (71) recorded their lowest-ever scores. Over the past decade significant improvement has only been observed in the Czech Republic (57), Estonia (76), Greece (49), Latvia (60), Italy (56) and Ireland (77).

In Poland (54), a seven-point decline over the last ten years has been attributed to the previous Law and Order party’s (PiS) efforts to monopolise power without taking public interest into account. The country’s new government is now tasked with restoring equilibrium and upholding the rule of law in the wake of disruptive judicial reforms implemented by PiS.

While Greece (49) has made progress in recent years, those gains have been damaged by the country’s rule of law crisis that has seen attacks on journalists and opposition politicians, along with a decline in press freedom. Weak levels of judicial independence have also contributed to Athens experiencing the most noticeable decline in the rule of law across the EU.

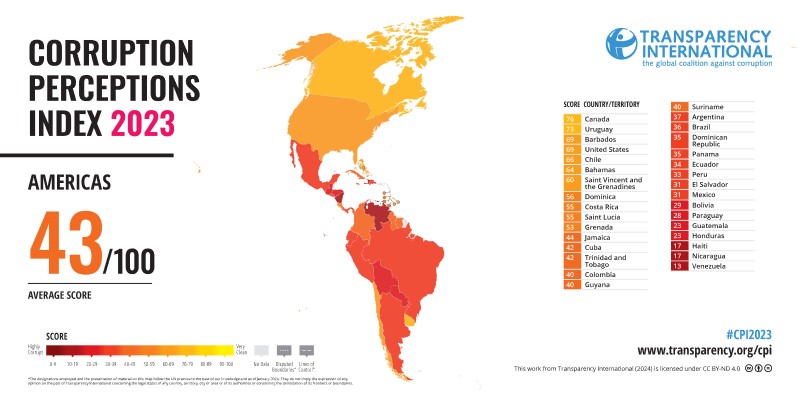

The Americas: lack of independent judiciary

The lack of independence of the judiciary is a major concern across the Americas region with only two countries, Guyana (40) and the Dominican Republic (35), improving their scores over the past decade. Prosecutors and judges are struggling to act with impartiality and to ensure fair trials across the region and this has contributed to a reduction in public trust.

Canada (76) and Uruguay (73) were the top scoring countries in the region with robust processes and high levels of judicial independence. Chile (66) has been notable for the strength of its democratic institutions and transparency, but the country has seen its score decrease since 2014 due to the exposure of several high-profile corruption cases that highlighted structural deficiencies. If it adopts the beneficial ownership law and implements the recommendations of the Advisory Probity and Transparency Commission, Chile is expected to return to progress in reducing its corruption levels.

As was the case in 2022, the United States again scored 69 points. The country’s federal and state judiciaries are largely continuing to act independently despite weak ethics rules for the Supreme Court raising serious questions about judicial integrity. Elsewhere, the region’s lowest scores were recorded in Venezuela, Haiti and Nicaragua.

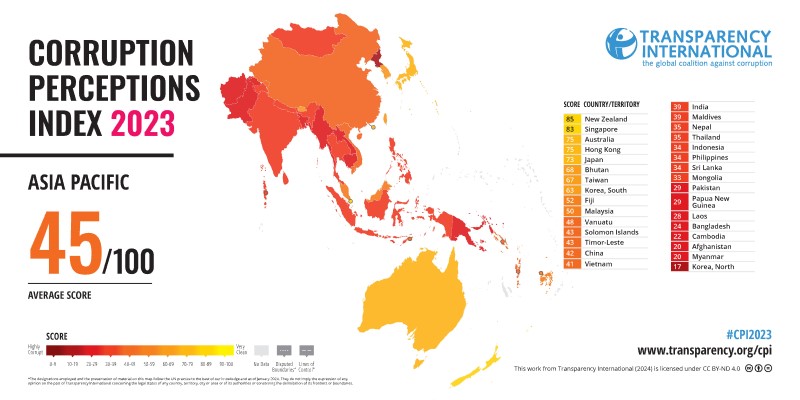

Change needed in the Asia Pacific region

Even though the Asia Pacific region had some top performers in the shape of New Zealand (85) and Singapore (83), it has continued to stagnate for the fifth year in a row with an average score of 45. New Zealand has actually experienced a slow decline in its score since 2020 due to a lack of confidence in the business community in the integrity of public contracting, taxation and trade opportunities. India (39), the world’s largest democracy, has remained idle on the CPI with a score of 39 and its government has continued to consolidate power while limiting the public’s ability to respond.

Malaysia (50) scored higher than the regional average as a result of robust elections and a functional anti-corruption commission. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of Indonesia (34) where it remains uncertain whether a severely weakened anti-corruption commission will be allowed to regain its mandate amid democratic backsliding. In Pakistan (29) and Sri Lanka (34), political instability has been balanced by strong levels of judicial oversight, helping keep the governments of both countries in check.

China (42) is an interesting case where a crackdown on corruption has seen more than 3.7 million public officials published over the past decade. However, Transparency International states that a closer study of the guilty verdicts shows that public officials often use corruption as a way to drive up their income while a heavy reliance on punishment as opposed to institutional checks on power raises doubts about the long-term effectiveness of anti-corruption measures.

Key developments in the Middle East and Africa

Authoritarianism, long-running conflicts, political misconduct and private interests overtaking the common good have continued to undermine anti-corruption efforts across the Middle East and parts of Africa. The region’s top scorers were the United Arab Emirates (68), Israel (62) and Qatar (58) while the three lowest-placed countries were Syria (13), Yemen (16) and Libya (18).

Most Arab countries failed to improve their positions in the index over the past decade due to high levels of political corruption that are hindering citizens’ access to essential services. While Arab states have made promises and devised strategies to combat corruption, the initiatives are frequently discarded by new administrations. Such inconsistencies create distrust between citizens and governments which also contributes to political instability. Seven Arab countries are among the bottom ten scorers on this year’s CPI.

Ongoing conflicts, including the war in Gaza, are exacerbating existing vulnerabilities in bordering countries across the region and contributing to emerging corruption practices. A continuous state of war in Yemen has trapped the country in an endless cycle of corruption while ongoing conflict in Libya has made oil a maneuvering tactic.

Kuwait (46) provides a more positive example, and it recorded its highest CPI score since 2015. Its National Assembly voted on a new government roadmap to improve development performance and achieve economic reform with a focus on transparency and better governance. Despite the inclusion of legislative changes, the framework does need to be refined with a focus on areas such as conflicts of interest, foreign bribery law, the right to information and the creation of the electoral commission.

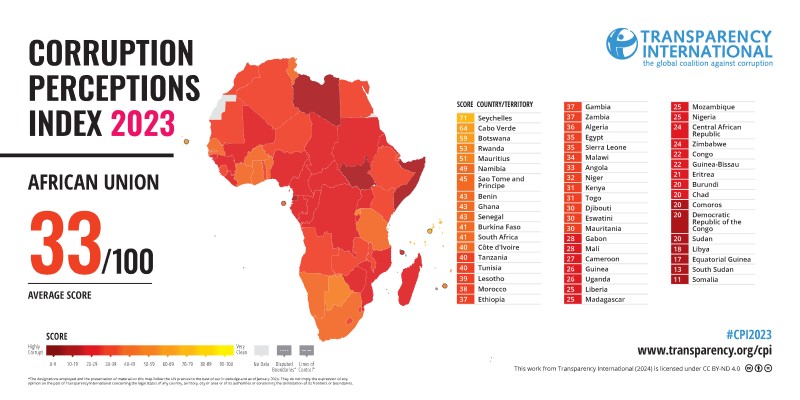

As has historically been the case in Sub-Saharan Africa, most nations remained stagnant or failed to make progress fighting corruption. 90% of countries in the region scored below 50. The main driving factors include widespread democratic backsliding and a weak justice system that is continuously employed to target the opposition or settle personal scores.

The trend is not universally bad across the region and significant improvement was noted in 2023 in the Seychelles (71), Angola (33) and the Côte d’Ivoire (40). The latter struggled with armed conflicts in the early 2010s and a political standoff in the wake of the 2010 elections. This finally resulted in a series of reforms including legislation increasing transparency whereby senior officials had to declare their assets. Accountability mechanisms were also strengthened through the creation of an economic and financial crimes section in the court system as well as a decree to clamp down on money laundering.

Recommendations

Transparency International remarks that corruption may be a multifaceted problem but it is one that we know how to solve. To that end, the organisation has a number of recommendations:

Strengthen the independence of the justice system: For a justice system to function, it is essential to shield it from interference, provide it with qualified personnel and ensure it is properly resourced. Appointments should be merit-based as opposed to being political.

Make justice more transparent: Transparency makes the justice system accountable and relevant data such as settlements and enforcement should be made openly available to discourage corruption.

Introduce integrity and monitoring mechanisms: Special protections required by members of the justice system should not be abused and this can be prevented through dedicated whistleblowing channels. Requirements should also be introduced for key legal stakeholders like judges and prosecutors to disclose their assets and interests.

Promote cooperation within the justice system: Given the complexity of justice systems, it is important to ensure their different components can collaborate effectively.

Improve access to justice: A first step against impunity and corruption, protecting the right to access justice should involve the simplification of procedures while making the process accessible to all.

Expand avenues for accountability in grand corruption cases: In countries where justice systems are unwilling or unable to effectively enforce the law, institutions in foreign jurisdictions should play a role in handling grand corruption proceedings.

Methodology

180 countries and territories were ranked by their perceived levels of public sector corruption according to experts and business people. The research relies on 13 independent data sources from 12 different institutions. They are then standardized on a scale of 0-100 before the average is calculated, along with the measure of uncertainty.

Key principles of establishing an effective ABC programme